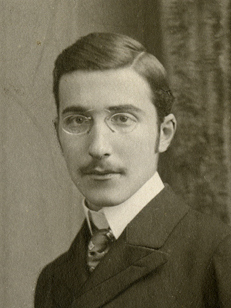

Bernie Sanders getting arrested in 1963 while trying to desegregate Chicago schools.

Tomorrow, New York State will have a fairly decisive vote in the Democratic primary process. If Bernie wins, that would be eight states in a row and would seriously undermine Hillary’s expectation of coronation rather than nomination. If he loses, this makes his path to the nomination much more difficult, if not nearly impossible. By now there have been various pieces from Hillary supporters ranging from thoughtful statements to moronic ALL CAPS SCREEDS. Bernie supporters have mirrored this spectrum with important reminders about Hillary’s record and, unfortunately, have written pieces that try and fail to rationalize his flawed position on guns. I hope what I say below will lean more towards one side of the spectrum than the other.

Why Bernie?

I have never before given money to a campaign, volunteered, or waited hours to attend a political rally. I have done all three for Bernie and plan to vote for him tomorrow for mainly one reason: morality. Whereas many people of good faith in the Clinton camp see Bernie’s attacks on inequality as a useful if monotone focal point in this year’s campaign, I see inequality, or better put, social justice as the basis for interest in politics per se. If the (im)moral vision of Donald Trump is enough to compel liberals to froth at the mouth and even suggest re-registering as Republicans to back Marco Rubio [as if he’s somehow “better” than Trump], why shouldn’t moral values determine the candidate that one is truly for? There are essentially three answers usually proposed in response by Clintonites.

The first stock answer from Clinton supporters has been as follows: Bernie represents everything I hope and wish for, but I think it won’t be achievable and Hillary might be able to actually do something. Many of the people who say this voted Obama, effectively moving from “Hope” to “Nope.” This question of idealism and pragmatism is certainly not a new one.

There is a section in Plato’s Republic—a pretty good book on politics—that directly takes up this tension between idealism and realism. After having theorized a fairly elaborate system of social organization in service of creating a perpetually just city, Socrates is asked by Glaucon if any of this is even possible. In response, he asks,

“Do you think that someone is a worse painter if, having painted a model of what the finest and most beautiful human being would be like and having rendered every detail of his picture adequately, he could not prove that such a man could come into being?

No, by god, I don’t.

Then what about our own case? Didn’t we say that we were making a theoretical model of a good city?”

The point, of course, is that the theoretical vision matters, and particularly at this moment—during a campaign—where every single candidate on all sides is in “I’m gonna”-mode. Remember when Barack Obama was going to close down GITMO and have the most transparent administration in history? The prison camp is still there, and his administration has prosecuted more whistleblowers and journalists under the Espionage Act than all previous presidents combined. I voted for Obama twice. The first time gleefully, the second, grudgingly. Who knows? I might have buyer’s remorse with Bernie, too. However, at this point in any campaign we only have the candidate’s record of past decisions, behaviors, and moral vision for the future. I think, as (strangely) do many Hillary supporters, Bernie wins in this regard.

The second objection usually levied by Clintonites against Bernie is the idea that he focuses too much on the economy. I think they have a point here to a certain extent. Social justice is not just economic justice; it also involves racial justice. We are in America, after all. However, the Sanders campaign offered a robust series of objectives for countering institutional racism months ago and has incorporated Black Lives Matter activists into the upper echelons of the campaign staff. Add to this the fact that Bernie literally marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was arrested in Chicago for protesting housing segregation, was one of the few Congressmen to back Jesse Jackson’s presidential bid, and has fought for social welfare legislation his entire career. This last point is important. Though it may be true that socio-economic justice is not equivalent to racial justice, it is equally true that racial justice cannot be achieved without socio-economic justice. A person who happened to believe this deeply was MLK.

The last indictment of Bernie by Clintonites is that he is unwilling to dirty his hands in order to get things done. In some cases, they actually revel in Hillary’s Machiavellian approach to politics and tendency to use military force to advance her given policy. Once again, MLK’s views are both important and relevant here: it is wrong to use immoral means to achieve moral ends. Bernie has refused SuperPAC money and lobbyist cash, because he rightly believes that they are not the solution to but the problem of contemporary American politics. He has also indicated that he would be much more reluctant to use force to “solve” political problems. He appears to be the only candidate running that understands what is unique about military force: the moment it is used, all things thought to be constants become variables. Consequently, there has to be a very good plan for the peace after the use of force. In other words, war should only be used as an instrument within a larger plan for a durable political solution. It’s odd to say, but it seems like Bernie knows his Clausewitz better than Hillary.

In sum, since in political campaigns we only have the moral vision and actions of the candidates to go on, it is precisely those candidates whose principles coincide most closely with our own that should be our obvious choice. With the options we have tomorrow, Bernie Sanders is the clear choice by all accounts.

Why Not Hillary?

Hillary supporters often worry that after the party “inevitably” anoints its candidate that Bernie supporters will not come around and unify the Democrats. Their fears are well founded. I would find it very difficult to vote for Hillary, though, to be frank, should she become the nominee I probably would vote for her in the general election. However, I am adamantly against her in the primary. Why?

First of all, let me dispense with red herring of sexism. Yes, Hillary Clinton has been subject to sexist ridicule that no male candidate has had to suffer through. This is incontestable and attests to the fact that we live in a depressingly misogynistic society. It does not, however, make her a choiceworthy candidate. I, too, would be overjoyed with and prefer to have the opportunity to vote in our first female president. I’d prefer to because it’s about goddamn time, and I want my daughter to see a woman at the pinnacle of power. I’d like that woman to be Elizabeth Warren. If she were the other Democratic candidate today, as much as I like Bernie, I’d drop him like a bad habit.

Now that that is out of the way, I want to provide my rationale as to why Hillary Clinton is not only a lesser candidate than Bernie but actually a bad one for anyone who has left-wing or progressive values. Since her days as First Lady, Hillary Clinton has been a standard-bearer of the neoliberal establishment, at once playing up a half-hearted social liberalism (cf. DOMA and “don’t ask, don’t tell”) and initiating class warfare from above. It is Clintonism that midwifed the deliberate abandonment of the working class by the Democratic party, turning what could have been a resuscitation of LBJ’s war on poverty into a war on the poor. Hillary Clinton was not an innocent bystander during this era. Instead she embraced racist dog whistling (“superpredators” and “bringing them to heel”) and denigrated struggling single mothers as “deadbeats.” Nor are these statements merely antiquarian outliers, but rather take current form in Hillary’s calls for poor students to have “skin in the game.”

The main reason I cannot vote for Hillary Clinton, however, is her view on foreign policy. While Hillary might be better on guns at home than Bernie, she’s immoral and incompetent on guns abroad. It is baffling to me that anyone with self-professed progressive values could be taken with what is often described as her “nuance” and “firm grasp” of foreign policy. Policy-wonkishness is not tantamount to good judgment. This brings me to her foreign policy guru: Henry Kissinger. When Hillary touts the original Darth Vader as a fan of her work—a man who literally has the blood of hundreds of thousands of innocents on his hands—I am awestruck that anyone could consider voting for her. Yes, Bernie stumbles when asked about foreign policy and sounds pretty bad. Hillary seems very comfortable with foreign policy questions and sounds much worse.

This latter point is the grand irony of the question of the pragmatism often brandished as the clinching element for the undecided-yet-leaning-Hillary voter. Henry Kissinger was the master of short-term, Machiavellian pragmatism. This approach brought the backing of the cruel regime of the shah of Iran, produced the rise to power of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and helped place General Pinochet and his death squads in power in Chile, to name just a few policy outcomes. Or, as Barrett Brown has brilliantly put it, he represents the-ends-justifies-the-means-and-oops-we-fucked-up-the-ends-too foreign policy establishment. It was this Kissingerian pragmatism that brought about Hillary’s Iraq War vote and her latest adventure in Libya. Thus far, up to 175,000 civilians have been killed in Iraq and nearly 30,000 have been killed in Libya; both countries have become havens for ISIS and various other terrorist groups.

So, New Yorkers, when you go to the polls tomorrow, please remember that you are voting for candidates who are making claims about what they will do. At this point, all we have to go on are their past actions, their claims, and the moral implications of both. And going on that, Bernie Sanders is the clear choice.